REGDOC-3.5.3, Regulatory Fundamentals, Version 3

Preface

The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) is the federal organization responsible for regulating the use of nuclear energy and materials in Canada. It regulates to protect health, safety, security and the environment, and to implement Canada's international commitments on the peaceful use of nuclear energy. The CNSC also disseminates objective scientific, technical, and regulatory information to the public.

Regulatory document REGDOC-3.5.3, Regulatory Fundamentals, outlines the CNSC’s regulatory philosophy and approach to applying the Nuclear Safety and Control Act. It provides information for licensees, applicants and the public, and contains neither guidance nor requirements. It replaces P 299, Regulatory Fundamentals (2005), INFO-0795, Licensing Basis - Objective and Definitions (2010), and P-242, Considering Cost-Benefit Information (2000).

This regulatory document is part of the CNSC’s processes and practices series of regulatory documents, which also covers information on licensing processes, compliance, and enforcement. The full list of regulatory documents is included at the end of this document, and can also be found on the CNSC’s website.

REGDOC-3.5.3, Regulatory Fundamentals, Version 3 is intended for information only and does not contain any requirements for CNSC licensees. The information in this regulatory document will be of interest to anyone seeking to learn more about the CNSC and how it regulates nuclear activity in Canada. It also describes the CNSC’s regulatory approach on key topics such as regulatory principles, protection of the health and safety of persons, protection of the environment, international obligations and the graded approach.

The words “shall” and “must” are used to express requirements to be satisfied by the licensee or licence applicant. “Should” is used to express guidance or that which is advised. “May” is used to express an option or that which is advised or permissible within the limits of this regulatory document. “Can” is used to express possibility or capability.

Nothing contained in this document is to be construed as relieving any licensee from any other pertinent requirements. It is the licensee’s responsibility to identify and comply with all applicable regulations and licence conditions.

Table of contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. About the CNSC.

- 3. The CNSC’s Regulatory Framework

- 4. Public and Indigenous Engagement

- 5. The CNSC’s Regulatory Approach

- 6. Licensing and Certification

- 7. Compliance

-

Appendix A: Consideration of Cost-Benefit Analysis

-

A.1 Considerations when preparing a cost-benefit analysis

- A.1.1 Level of analysis

- A.1.2 Rationale

- A.1.3 Boundaries

- A.1.4 Potential factors for consideration in the cost-benefit analysis

- A.1.5 Consideration of alternatives

- A.1.6 Forecasting

- A.1.7 Valuation

- A.1.8 Value-based weighting

- A.1.9 Uncertainty

- A.1.10 Sensitivity analysis

- A.1.11 Replicability

- A.1.12 Discount rate

- A.2 Considerations of costs and benefits for licence applications and decisions

- A.3 Considerations of costs and benefits in regulatory documents

- A.4 Examples and resources for developing a cost-benefit analysis

-

A.1 Considerations when preparing a cost-benefit analysis

- Appendix B: Safety and Control Area Framework

- Appendix C: Levels of Defence in Depth for Nuclear Power Plants

- Appendix D: Risk-Informed Regulating

- Glossary

- References

- Additional Information

1. Introduction

1.1 Purpose

This regulatory document is intended for information only and does not contain any requirements for CNSC licensees. It describes the CNSC’s regulatory approach and philosophy, and outlines how the CNSC applies the Nuclear Safety and Control Act (NSCA) and regulations made under the authority of the NSCA in its regulatory oversight. The information in this regulatory document will be of interest to anyone seeking to learn more about the CNSC and how it regulates nuclear activity in Canada

1.2 Scope

This document describes the CNSC’s regulatory activities.

2. About the CNSC

Regulation is a key instrument used by government to enable economic activity and to protect health, safety, security and the environment in Canada. The Government of Canada has determined that the use of nuclear substances and nuclear energy offers benefits, and that the associated risks must not be at an unreasonable level. These two facts drive the need for Canadian legislation and a regulatory body to oversee nuclear activities in Canada.

The NSCA came into force on May 31, 2000. It established the Commission, its objects, and the framework under which it can effectively and independently meet those objects. The Commission reports to Parliament through the Minister of Natural Resources. The CNSC replaced the former Atomic Energy Control Board, which was founded in 1946.

The CNSC is the sole authority in Canada to regulate the development, production and use of nuclear energy, and the production, possession and use of nuclear substances, prescribed equipment and prescribed information in order to prevent unreasonable risk. The CNSC also disseminates objective scientific, technical and regulatory information to the public.

The CNSC has also been delegated authority to implement Canada’s agreement with the International Atomic Energy Agency on nuclear safeguards verification. For more information, see the Agreement Between the Government of Canada and the International Atomic Energy Agency for the Application of Safeguards in Connection with the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons [1] and the Protocol Additional to the Agreement between Canada and the International Atomic Energy Agency for the Application of Safeguards in Connection with the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons[2].

2.1 The Commission

The CommissionFootnote 1 is an independent, quasi-judicial, administrative tribunal and a court of record, with the powers, rights, and privileges necessary to carry out its duties and enforce its orders. It operates at arm’s length from the government with no ties to the nuclear industry.

The Commission has up to seven permanent members, who are appointed by the Governor in Council for terms of up to five years. One member is designated as President of the Commission and Chief Executive Officer of the CNSC.

Subject to the approval of the Governor in Council,Footnote 2 the Commission may make and amend regulations as it deems necessary for attaining the objects of the NSCA. The Commission is also empowered to grant licences to conduct nuclear activities.

The Governor in Council may issue directives to the CNSC. Any such directive may only be of general application on broad policy matters with respect to the objects of the Commission, and not in respect of a particular case before the Commission.

Commission decisions are science- and safety-based; they may not be overturned by the Government of Canada, and they are reviewable only by the Federal Court of Canada. These measures help ensure the independence of the Commission. To maintain its adjudicative distance from CNSC staff, the Commission communicates with staff only through the Commission Registry and through formal proceedings. This separation also serves to maintain the Commission’s independence.

2.2 CNSC staff

The Commission employs the staff it considers necessary for the purposes of the NSCA.

The CNSC has highly skilled scientific, technical, professional and administrative personnel who carry out the work necessary to fulfill the Commission’s mandate. CNSC staff perform several functions such as:

- reviewing licence applications

- conducting expert research and analysis

- verifying licensee compliance with regulatory requirements

- conducting activities to enforce licensee compliance, when necessary

- preparing material, known as Commission member documents (CMDs), for the Commission and appearing before the Commission at proceedings to answer questions

- carrying out a wide range of internal activities that enable the success of the CNSC’s core operational work

The Commission may also enter into contracts for services to receive advice and assistance in the exercise or performance of any of its powers, duties or functions under the NSCA.

2.3 What the CNSC regulates

The CNSC regulates the conduct of activities related to the use, production and distribution of nuclear energy and substances as described in paragraphs 26(a) to (f) of the NSCA. This includes activities related to:

- uranium mines and mills

- uranium fuel fabrication and processing

- nuclear power plants

- nuclear substance processing

- industrial and medical applications

- nuclear research and educational activities

- transportation of nuclear substances

- nuclear security and safeguards

- import and export activities

- waste management facilities

3. The CNSC’s Regulatory Framework

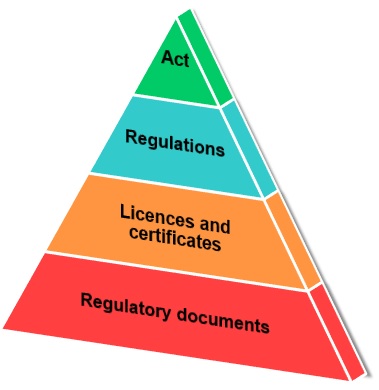

The CNSC’s regulatory framework (see figure 1) consists of the Nuclear Safety and Control Act (NSCA) and other laws passed by Parliament that govern the regulation of Canada's nuclear industry, as well as regulations, licences and documents that the CNSC uses to regulate the industry.

The regulatory framework also includes guidance, which is used to inform the applicant or licensees on how to meet requirements, elaborate further on requirements, or provide best practices. While the CNSC sets requirements and provides guidance on how to meet requirements, an applicant or licensee may put forward a case to demonstrate that the intent of a requirement is addressed by other means. Such a case must be demonstrated with supportable evidence. The applicant or licensee may submit cost-benefit analysis to support its case. See appendix A for more information on how the CNSC considers cost-benefit analysis.

CNSC staff consider guidance when evaluating the adequacy of any case submitted. This does not mean that the requirement is waived; rather, it is an indication that the regulatory framework provides flexibility for licensees to propose alternative means of achieving the intent of the requirement. The Commission is always the final authority as to whether the requirement has been met.

CNSC requirements and guidance take into account international regulatory best practices and modern codes and standards, and align with the International Atomic Energy Agency’s Safety Fundamentals and Safety Requirements. The CNSC cooperates with other organizations and jurisdictions to foster the development and application of a consistent, effective regulatory framework in Canada. The CNSC welcomes feedback on its regulatory framework at any time.

Further information on the CNSC’s regulatory framework can be found on the CNSC’s Regulatory framework overview Web page

3.1 The Nuclear Safety and Control Act

The NSCA establishes the CNSC’s mandate to regulate the development, production, and use of nuclear energy and the production, possession and use of nuclear substances, prescribed equipment and prescribed information in Canada.

The mandate of the CNSC is informed by the objects of the Commission, set out in section 9 of the NSCA, which are:

-

(a) to regulate the development, production and use of nuclear energy and the production, possession and use of

nuclear substances, prescribed equipment and prescribed information in order to

- (i) prevent unreasonable risk, to the environment and to the health and safety of persons, associated with that development, production, possession or use,

- (ii) prevent unreasonable risk to national security associated with that development, production, possession or use, and

- (iii) achieve conformity with measures of control and international obligations to which Canada has agreed; and

- (b) to disseminate objective scientific, technical and regulatory information to the public concerning the activities of the Commission and the effects, on the environment and on the health and safety of persons, of the development, production, possession and use referred to in paragraph (a).

When making licensing decisions, the Commission is guided by subsection 24(4) of the NSCA, which states:

-

(4) No licence shall be issued, renewed, amended or replaced — and no authorization to transfer one given —

unless, in the opinion of the Commission, the applicant or, in the case of an application for an authorization

to transfer the licence, the transferee

- (a) is qualified to carry on the activity that the licence will authorize the licensee to carry on; and

- (b) will, in carrying on that activity, make adequate provision for the protection of the environment, the health and safety of persons and the maintenance of national security and measures required to implement international obligations to which Canada has agreed.

3.2 Regulations made under the Nuclear Safety and Control Act

The regulations made under the NSCA set requirements with respect to topic-specific considerations, using a combination of prescriptive and performance-based approaches. Prescriptive approaches tell licensees exactly what they need to do to meet requirements, whereas performance-based approaches set specific performance measures that licensees must meet with respect to particular aspects of their licensed activities.

There are 13 regulations under the NSCA, including the General Nuclear Safety and Control Regulations and the Radiation Protection Regulations. Regulations under the NSCA describe the general application of requirements for nuclear activity in Canada, and also provide requirements for Class I and Class II nuclear facilities, uranium mines and mills, and the use of nuclear substances. The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission By-laws and the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission Rules of Procedure define the management and conduct of the Commission’s affairs.

The CNSC regularly reviews its suite of regulations and makes amendments as needed to ensure that Canadians and CNSC-regulated parties continue to be supported by an effective, efficient and modern regulatory framework. When developing regulations, the CNSC considers various factors, including costs and benefits, gender-based analysis plus (GBA+), impacts on the environment, modern treaty implications, and regulatory cooperation. The Treasury Board of Canada oversees the process for the development, management and review of regulations. Its requirements are set out in the Cabinet Directive on Regulation (2018).

More information about all regulations under the NSCA can be found on the List of regulations on the CNSC website

3.3 Licences and certificates

3.3.1 Licences

Section 26 of the NSCA prohibits any person from conducting certain activities except in accordance with a licence. The NSCA gives the Commission the power to grant licences for these activities.

All applicable licence conditions are reflected in the respective licence, including those that require the licensee to ensure that qualified personnel carry out the licensed activities, and that adequate provision is made for the protection of the environment, the health and safety of persons, and the maintenance of Canada’s domestic and international obligations.

For more information on licensing, see section 6.1 of this document.

The CNSC also issues certificates for people to carry out prescribed duties and for the use of prescribed equipment, and for the packaging and transport of nuclear substances. In each case, the certificate sets out applicable regulatory requirements. See section 5.4 for more information on certification.

3.4 CNSC regulatory documents and domestic and international standards

In addition to the NSCA and the regulations made under it, the CNSC has developed regulatory documents, which are a key part of its regulatory framework for nuclear activities in Canada. They provide additional clarity to licensees and applicants by explaining how to meet the requirements set out in the NSCA and the regulations made under it. Regulatory documents are organized into three key categories: regulated facilities and activities, safety and control areas, and other areas of regulatory engagement.

The CNSC maintains an efficient and streamlined regulatory framework by making appropriate use of standards. These include, but are not limited to, standards created by independent, third-party standard-setting organizations such as the CSA Group, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, the International Commission on Radiological Protection and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Domestic or international standards may be referenced in CNSC regulatory documents.

More information about the CNSC’s regulatory documents and CSA Group nuclear standards can be found on the CNSC’s Regulatory documents Web page.

3.5 Safety and control areas

Safety and control areas (SCAs) are the technical topics that CNSC staff use to assess, review, verify and report on regulatory requirements and performance across all regulated facilities and activities. By providing a common language and architecture, SCAs improve understanding and communication within the CNSC, as well as between the CNSC and licensees, the Commission, other stakeholders, and Indigenous peoples. The CNSC’s 14 SCAs are organized in three functional areas: management, facility and equipment, and core control processes.

SCAs do not constrain the CNSC in its conduct of regulatory oversight activities. Additional topics may be added as needed to provide satisfactory assurance of compliance.

Appendix B provides a table that lists the SCAs and their respective specific areas.

3.6 Role of consultation in the regulatory framework

Consultation with the public, licensees, Indigenous peoples and stakeholders is an integral component of developing the CNSC’s regulatory framework. Regulations and regulatory documents published by the CNSC are generally subject to a formal public consultation process. Meetings and workshops may be organized to engage stakeholders and Indigenous peoples, and solicit feedback on the development of regulatory requirements and guidance, and on what regulatory instruments are appropriate.

When proposing changes to the regulatory framework, the CNSC uses a variety of means to actively seek input from licensees, the public, non-governmental organizations, all levels of government, and international stakeholders. All input gained from these activities is considered when the CNSC develops and maintains its regulatory instruments. The CNSC uses discussion papers to solicit early feedback from stakeholders and Indigenous peoples about the development of new or amended regulations, and when it is considering new areas of oversight or exercising its existing regulatory authority in a new manner.

The CNSC communicates openly and transparently with stakeholders and Indigenous peoples, while respecting Canada’s access to information and privacy laws. It consults stakeholders and Indigenous peoples when establishing priorities, developing policies and planning programs and services. The CNSC also cooperates with other jurisdictions to increase efficiency and effectiveness; for example, entering into formal arrangements where appropriate.

4. Public and Indigenous Engagement

4.1 Commission proceedings

Commission proceedings include public hearings and public meetings. At public hearings, the Commission hears information pertaining to the making of licensing and certification decisions. Public meetings are used to brief the Commission about significant developments that affect the nuclear regulatory process, or to ask the Commission to make administrative decisions or deal with administrative issues. Hearings and meetings can also be viewed online as webcasts.

All Commission hearings are public hearings, as they become public when a notice of hearing is published. The Commission may decide to allow interventions at public hearings. If interventions are allowed the Commission decides whether to allow written interventions only or also oral interventions. The Commission may also decide to allow interventions for certain meeting items at public meetings. An example of such a meeting item is one of the Regulatory Oversight Reports, where written interventions from the public, as well as written and oral interventions from Indigenous peoples, were allowed.

4.2 Dissemination of objective scientific, technical and regulatory information

As part of its mandate to disseminate objective scientific, technical, and regulatory information, the CNSC informs the public about the development, production, possession, transport and use of nuclear substances on an ongoing basis. This is accomplished through various means, including:

- regulatory documents, decisions, reports, and plans posted to the CNSC website

- public Commission hearings and meetings

- live webcasts during Commission hearings and meetings

- social media platforms (YouTube, Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn) and online resources (available on the CNSC website) that provide technical and scientific information in plain language

- public information sessions

- public consultation on, and publication of, regulations and regulatory documents

- sessions across Canada, to familiarize people with the CNSC and its role, and how they can participate in CNSC regulatory processes

In addition, the CNSC encourages its experts to share their knowledge, and it publishes scientific and technical paper abstracts, as well as journal articles authored by CNSC staff on its website. Staff also attend national fairs and conferences that specifically target youth, municipalities, and the medical community. This ongoing dialogue is important for increasing public understanding and trust in the CNSC’s role of protecting Canadians, their health, and the environment.

4.3 Indigenous consultation and engagement

The CNSC seeks opportunities to work with Indigenous peoples to understand any concerns they may have about the nuclear sector, and to ensure the safe and effective regulation of nuclear energy and materials.

As an agent of the Crown, the CNSC is responsible for fulfilling its legal duty to consult, and where appropriate, accommodate Indigenous peoples when its decisions may have an adverse impact on potential or established Indigenous and/or treaty rights pursuant to section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.

The CNSC’s approach to Indigenous consultation includes commitments to uphold the honour of the Crown through information sharing, relationship building and promoting reconciliation, as well as to meeting its common-law duty to consult. The CNSC supports a coordinated, whole-of-government approach to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the consultation process.

The CNSC cannot delegate its obligation, but can assign procedural aspects of the consultation process to licensees. In many cases, licensees are best positioned to collect information and propose any appropriate additional measures. The information collected and measures proposed by licensees to avoid, mitigate or offset adverse impacts is used by the CNSC in meeting its obligations and in its efforts toward reconciliation.

For further information on the CNSC’s approach to Indigenous consultation and engagement, see REGDOC-3.2.2, Indigenous Engagement [3].

5. The CNSC’s Regulatory Approach

As discussed earlier in this document, the CNSC regulates to prevent unreasonable risk to the environment, the health and safety of persons, and national security. To this end, the CNSC has established a licensing and compliance system to ensure that all persons who use or possess nuclear substances and radiation devices do so in accordance with a licence, and that regulated parties have safety and security provisions in place that ensure compliance with regulatory requirements.

This section addresses the major elements that comprise the CNSC’s regulatory approach.

5.1 Regulatory principle

The CNSC’s regulatory philosophy is based on the following:

- Licensees are directly responsible for managing regulated activities in a manner that protects health, safety, security and the environment, and that conforms with Canada’s domestic and international obligations on the peaceful use of nuclear energy.

- The CNSC is accountable to Parliament and to Canadians for assuring that these responsibilities are properly discharged.

The CNSC therefore ensures that regulated parties are informed about requirements and provided with guidance on how to meet them, and then verifies that all regulatory requirements are and continue to be met.

5.2 Continuous improvement

The CNSC is committed to continuous improvement of both its internal operations and its regulation of the Canadian nuclear industry. The CNSC therefore requires licensees to strive to further reduce the risks associated with their licensed activities on an ongoing basis. It assesses how licensees manage risk during both normal operations and in response to potential accident conditions applying concepts such as the ALARAFootnote 3 principle and defence in depth (see section 4.3). In its assessments, the CNSC considers how licensees continuously evaluate, manage, and further reduce uncertainties with respect to hazards and safety issues. This also includes assessing how licensees consider additional safety and mitigation options as techniques and technologies evolve.

5.3 Defence in depth

CNSC requirements necessitate the implementation of defence in depth (DiD) in the design, construction and operation of nuclear facilities or the undertaking of nuclear activities. With DiD, more than one level of defence (i.e., protective measure) is in place for a given safety objective, so that the objective will still be achieved even if one of the protective measures fails.

To achieve this, multiple independent levels of defence must be put into place to the extent practicable, taking organizational, behavioural, and engineered safety and security elements into account, such that no potential human or mechanical failure relies exclusively on a single level of defence.

DiD applies to a wide range of facilities and activities. Appendix C illustrates how the different levels are defined for nuclear power plants.

5.3.1 Emergency preparedness

With regard to emergency preparedness and response, the CNSC has multiple emergency-related roles that translate to reducing risk in the event of an emergency. The CNSC regulates licensees’ onsite emergency plans at nuclear facilities, ensures that applicants provide support to and have arrangements in place with offsite authorities (such as municipal and provincial governments), and is also part of the whole-of-government approach to federal nuclear emergency planning.

In the unlikely event of a nuclear emergency, the CNSC’s role is to monitor and evaluate the actions of any nuclear operators involved, provide technical advice and regulatory directives when required, and inform the government and the public of its assessment of the situation. The CNSC’s emergency preparedness program ensures well-coordinated, suitable responses to emergencies by integrating with nuclear operators; municipal, provincial and federal government agencies; first responders; and international organizations. The program is regularly tested through exercises that involve simulated incidents in coordination with licensees and government agencies.

5.4 Graded approach

The graded approach is a systematic method or process by which elements such as the level of analysis, the depth of documentation and the scope of actions necessary to comply with requirements are commensurate with:

- the relative risks to health, safety, security, the environment and the implementation of international obligations to which Canada has agreed

- the particular characteristics of a nuclear facility or licensed activity

The CNSC applies the graded approach to licensing and compliance activities.

This approach is driven primarily by assessment of the risk associated with the activities being regulated, and the performance history of the licensee.

The degree of oversight is also informed by:

- the complexity and potential harm posed by the licensed activity

- technical assessments of submissions

- relevant research

- information supplied by parties to Commission proceedings

- international activities that advance knowledge in nuclear and environmental safety

- cooperation with other regulatory bodies

When applying the risk-informed approach, the following principles are adhered to:

- the meeting of regulatory requirements

- the maintenance of sufficient safety margins

- the maintenance of defence in depth

If a licensee cannot achieve the required level of safety, it will not be permitted in any case to continue conducting its licensed activities.

Further information can be found in Appendix D: Risk-Informed Regulating

5.5 Protection of the environment

Environmental protection is a shared federal–provincial responsibility. The CNSC cooperates with other jurisdictions and departments and, where appropriate, enters into formal arrangements to protect the environment more effectively and to coordinate regulatory oversight.

The CNSC’s environmental protection mandate includes design objectives and best practices to minimize or eliminate the release of nuclear or hazardous substances to the environment. Environmental protection measures are commensurate with the level of risk associated with the activity. The CNSC determines whether a licensee or applicant will make adequate provision to protect the environment against unreasonable risk, and verifies compliance with associated regulatory requirements.

Under the Impact Assessment Act, the Minister of the Environment must refer the impact assessment of a designated project to a review panel if the project includes physical activities that are regulated under the NSCA. The Memorandum of Understanding on Integrated Impact Assessments under the Impact Assessment Act between the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada and the CNSC provides procedures and guidance and allows for a single, comprehensive process for integrated impact assessment.

The Impact Assessment Act replaced its predecessor, the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012 (CEAA 2012), in August 2019. However, at that time there were active environmental assessments being performed by the CNSC under CEAA 2012. Therefore, the CNSC will continue to carry out those active environmental assessments under CEAA 2012 until they are completed.

For further information on environmental protection, see REGDOC-2.9.1, Environmental Principles, Assessments and Protection Measures [4].

5.6 Protection of the health and safety of persons

The CNSC sets dose limits that are within the protective health limits and establishes regulations that set requirements to prevent unreasonable risk to the health and safety of persons. These limits are described in the Radiation Protection Regulations and are consistent with the recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP).

The Radiation Protection Regulations also require every licensee to implement a radiation protection program that takes into consideration the ALARA principle.

In addition to radiological hazards, regulating to prevent unreasonable risk to the health and safety of persons addresses conventional health and safety hazards.

5.7 Protection of national security

To prevent risk to national security, the CNSC works closely with nuclear facility operators, law enforcement and intelligence agencies, international organizations, and other governmental departments to ensure that nuclear substances and facilities are adequately protected. Nuclear security in Canada is aided by the Nuclear Security Regulations under the Nuclear Safety and Control Act. These regulations set out detailed security requirements for licensed nuclear facilities and other regulated activities.

5.8 International obligations

The CNSC participates in international fora to provide global nuclear leadership and to benefit from international experience and best practices. It also participates in undertakings implemented by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) (for example, IAEA peer reviews), the ICRP and other international organizations, as well as in activities under certain treaties such as the Convention on Nuclear Safety [5].

These international activities help inform the CNSC’s decision-making processes to:

- understand and compare various ways of evaluating and mitigating risks

- share research and operational experience

5.9 Nuclear non-proliferation

The CNSC is responsible for implementing Canada’s nuclear non-proliferation commitments and government policy:

- to assure Canadians and the international community that Canada’s nuclear exports do not contribute to the development of nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices

- to promote a more effective and comprehensive international nuclear non-proliferation regime

The international Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons [6] (NPT) is the cornerstone of Canada’s efforts to promote its objectives of international disarmament, non-proliferation, and the peaceful use of nuclear energy. NPT commitments to which Canada has agreed include:

- to not receive, manufacture, or acquire nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices

- to accept IAEA safeguards on all nuclear material for peaceful use in Canada

- to ensure that Canada’s nuclear material exports are subject to IAEA oversight

The CNSC implements these commitments through the NSCA and corresponding regulations, including the Nuclear Non-proliferation Import and Export Control Regulations.

5.10 Safeguards

The term “safeguards” refers to the measures taken by the IAEA, in accordance with the NPT, to verify that nuclear material is not diverted from peaceful uses to the development of nuclear weapons. The safeguards agreements between the Government of Canada and the IAEA give the IAEA the right and obligation to monitor Canada’s nuclear-related activities, and to verify nuclear material inventories and flows in Canada.

Through its regulatory oversight, the CNSC ensures that all applicable licensees have safeguards programs in place to allow for:

- monitoring and reporting on nuclear material and activities

- providing IAEA safeguards inspectors with access to areas where nuclear material is stored, and to certain specified nuclear-related manufacturing and research activities

- providing operational and design information for nuclear facilities to the IAEA

Where required by the safeguards agreements, the CNSC compiles licensee information and submits it to the IAEA on behalf of the Government of Canada. The CNSC also cooperates with the IAEA in developing new safeguards approaches for Canadian facilities, and contributes to efforts to strengthen IAEA safeguards internationally.

The CNSC’s REGDOC-2.13.1, Safeguards and Nuclear Material Accountancy [7], provides further information on Canadian safeguards regarding nuclear material.

6. Licensing and Certification

The Commission makes independent, objective and risk-informed decisions, taking into consideration all of the information provided by applicants, stakeholders, Indigenous peoples, and staff. CNSC staff make recommendations to the Commission based on thorough assessment of factual evidence. The Commission recognizes the role of professional judgment, particularly in areas where no objective standards exist.

6.1 Licensing

The licensing process consists of submission of a licence application, an assessment of the application by CNSC staff, and a decision by the Commission or a designated officer.

6.1.1 Licensing basis

The licensing basis sets the boundary conditions for a regulated activity, and establishes the basis for the CNSC’s compliance program for that regulated activity.

All licensees are required to conduct their activities in accordance with the licensing basis, which is defined as a set of requirements and documents for a regulated activity comprising the following:

- The regulatory requirements set out in the applicable laws and regulations

- The conditions and safety and control measures described in the licence, and the documents directly referenced in that licence

- The safety and control measures described in the licence application and the documents needed to support that licence application

Documents needed to support the licence application are those documents that demonstrate that the applicant is qualified to carry out the licensed activity, and that appropriate provisions are in place to protect worker and public health and safety, to protect the environment, and to maintain national security and measures required to implement international obligations to which Canada has agreed. Examples are detailed documents supporting the design, safety analyses and all aspects of operation to which the licensee makes reference, documents describing conduct of operations, and documents describing conduct of maintenance.

6.1.2 Licence condition handbook

The CNSC’s licensing regime includes the licence conditions handbook (LCH), which is a companion piece to interpret a licence. The general purpose of the LCH is, for each licence condition, to clarify the regulatory requirements and other relevant parts of the licensing basis.

The LCH, which should be read in conjunction with the licence, provides compliance verification criteria that the licensee must follow to comply with licence conditions, operational limits and information on delegation of authority and applicable versions of documents referenced in the licence. The LCH also provides non-mandatory recommendations and guidance on how to comply with licence conditions and criteria.

6.2 Certification

Certification applies to persons carrying out prescribed duties and the use of prescribed equipment, and to the packaging and transport of nuclear substances.

6.2.1 Certification of persons

Persons in specific positions identified in regulations or a licence must hold a CNSC certification. The purpose of personnel certification is to regulate personnel who are assigned to positions that have a direct impact on the safe operation of a facility, or on the health and safety of workers, the public or the environment.

The CNSC’s regulatory framework defines CNSC requirements and expectations for certification processes, including the qualifications, training, and examinations necessary to become certified, and the work experience, training and testing necessary to maintain a certification.

6.2.2 Certification of prescribed equipment

Certification of equipment is an attestation from the CNSC that prescribed equipmentFootnote 4 is safe for use by qualified personnel. No prescribed equipment – barring exemptions such as smoke detectors and other equipment with a very small amount of a nuclear substance – can be used in Canada unless it is a certified model or used in accordance with a CNSC licence.

6.2.3 Certification of transport packaging

The CNSC issues licences and certificates for packaging and transport of nuclear substances, as stipulated in the Packaging and Transport of Nuclear Substances Regulations, 2015 (PTNSR 2015). These regulations are based on the IAEA’s Regulations for the Safe Transport of Radioactive Material (2018 Edition) (IAEA Regulations).

The CNSC’s REGDOC-2.14.1, Information Incorporated by Reference in Canada’s Packaging and Transport of Nuclear Substances Regulations, 2015,[8] helps the regulated community comply with the PTNSR 2015. REGDOC-2.14.1 links provisions in the regulations to relevant content in the IAEA Regulations, the Nuclear Safety and Control Act (NSCA), other CNSC regulations, and other related information.

The CNSC regulates all aspects of the packaging and transport of nuclear substances, including the design, production, use, inspection, maintenance and repair of packages. In addition, the PTNSR 2015 require certain types of package design to be certified by the CNSC before being used in Canada. The PTNSR 2015 also provide for the certification of special form radioactive material confirming that the sealed source containing the radioactive material is designed to be strong enough to maintain leak tightness under the conditions of use and wear for which the sealed source was designed.

6.3 Pre-licensing and pre-certification

Pre-licensing activities, by proponents, with the CNSC, can vary in complexity from process-related questions to technical assessments that provide feedback to a potential applicant.

Pre-licensing and pre-certification activities may allow potential regulatory or technical issues to be identified early on, and improve an applicant’s understanding of the CNSC’s regulatory processes and requirements.

An example of a pre-licensing technical assessment is a CNSC review of a proposed facility design to identify problems and means for their resolution. Refer to REGDOC-3.5.4, Pre-licensing Review of a Vendor’s Reactor Design for more information.

6.4 Application assessment by CNSC staff

When the CNSC receives a licence application, staff evaluate it to determine if the proposed safety and control measures described in the application, and the documents needed to support the application, are adequate and meet applicable requirements.

Documents needed to support the licence application are those documents that demonstrate that the applicant is qualified to carry out the licensed activity, and that appropriate provisions will be made to protect worker and public health and safety, to protect the environment, and to maintain national security and measures required to implement international obligations to which Canada has agreed. Examples include detailed documents supporting the design, safety analyses and all aspects of operation to which the applicant makes reference; documents describing conduct of operations; and documents describing conduct of maintenance.

Regulatory documents and domestic and international standards may be referenced in the information supplied by an applicant in support of its licence application, and are used by CNSC staff to evaluate the application. These regulatory documents and standards become part of the licensing basis when referenced in the licence application or its supporting documentation, or when directly referenced in a licence.

Information submitted in support of an application must demonstrate that proposed safety and control measures will meet or exceed CNSC expectations. All submissions are expected to be supported by appropriate analytical, experimental or other suitable evidence. When deciding whether to renew an existing licence, the Commission also considers past performance by verifying compliance history.

Technical assessments are conducted to support licensing, compliance, regulatory decision making and development of regulatory positions. CNSC staff perform these assessments based on the best available science (such as technical knowledge and analytical methods), taking operating experience into consideration. Technical assessments determine whether submitted documents and supporting evidence presented to the CNSC by applicants or licensees have a sound technical basis, measured against the CNSC regulatory framework. These assessments address the completeness (coverage and adequacy), comprehensiveness (depth), and the validity of the rationale and technical justification provided in submissions, and are also used to verify licensee compliance with regulatory requirements.

If CNSC staff conclude that an application is not complete or satisfactory, the applicant will be asked to submit additional information. Normally, applications do not proceed to a decision until staff are satisfied that the application contains all of the relevant information needed for the Commission or a designated officer to make a licensing decision

6.5 Licensing and certification decisions

Licensing decisions include the issuance, refusal, amendment, renewal, suspension, revocation, replacement or transfer of a licence. Certification and decertification are determined by way of certification decisions. The CNSC’s independence and transparency in decision making are supported by fair, open, transparent and predictable regulatory processes. Commission hearings provide stakeholders and Indigenous peoples with the opportunity to be heard, and the Commission takes the input from stakeholders and Indigenous peoples into consideration in its decision-making.

The Commission is the decision-making authority for all licensing matters. For decisions related to some activities, the Commission designates its decision-making authority to certain CNSC staff members called designated officers (DOs). For more risk significant facilities and activities, decisions are made by the Commission.

The Commission considers evidence provided by applicants or licensees and other participants, and also considers the recommendations from CNSC staff in its decision making. The Commission or the DO then decides whether or not to issue the licence or certificate, adding conditions as appropriate.

Licensing decisions involve public hearings before the Commission as required by the NSCA. Commission proceedings are open to the public and are webcast live on the CNSC website.

7. Compliance

Once a license is issued, CNSC staff continue oversight through a compliance program. Compliance is defined as conformity by regulated persons or organizations with the requirements of the Nuclear Safety and Control Act (NSCA), the regulations made under the NSCA, licences, certificates, decisions, and orders made by the CNSC.

The licensee bears the primary responsibility for safety at all times, including compliance with regulatory requirements. The CNSC undertakes necessary and reasonable measures to ensure compliance. These measures include influencing compliance awareness, verification and enforcement (see sections 7.2 to 7.4 for more information on compliance verification and enforcement).

The CNSC holds information sessions and communicates with licensees regularly, in order to increase licensees’ awareness of their responsibilities and to promote compliance.

7.1 Planning of compliance verification activities

The CNSC’s compliance planning process ensures that compliance activities are carried out in a systematic and risk-informed manner. Annual compliance work plans outline the scope, scheduling, resourcing and timeframe for the activities to be undertaken for the next compliance cycle for a particular licence or class of licence.

The CNSC has developed a set of compliance verification activities that are based on the ongoing review of previous compliance findings and operational information. Once approved by the CNSC, any changes proposed by the licensee during the course of the given year are evaluated and documented using a risk-informed approach. Progress reviews are conducted periodically to monitor execution of the plan.

7.2 Compliance verification

The CNSC inspects and reviews operational activities and documentation to verify licensee compliance with requirements. The frequency, scope, type and depth of these inspections and reviews are risk-informed. Where there may be overlap in regulatory oversight with other regulatory bodies, the CNSC coordinates its verification activities to optimize efficiency and reduce administrative burden on licensees.

To evaluate licensee compliance, the CNSC conducts both field verification activities and desktop reviews.

Field verification activities include inspections and other surveillance and monitoring activities. Inspection is the process by which the CNSC inspectors gather data from the site of a licensed activity and analyze the data, for the purpose of confirming that workers, activities, facilities, and equipment are in compliance with the given licensing basis.

CNSC inspections are led by designated inspectors and are planned, controlled, coordinated, consistent, transparent (open to formal scrutiny) and conducted in alignment with the SCAs. The objectives of inspections are defined and communicated to licensees. Licensees are also made aware of inspection criteria, and of the standards of performance and methodologies being used.

Desktop reviews generally entail consideration of documents and reports, such as quarterly technical reports, annual compliance reports, special reports, and documentation related to design, safety analysis, programs and procedures. Licensees are required to provide information to the CNSC through baseline reporting (scheduled) and event reporting. They are also expected to notify the CNSC of changes to operating processes, procedures or programs, or to submit written requests of such changes. In all cases, the CNSC assesses this information to ensure that operations remain within the licensing basis.

Where a deficiency or deviation is either self-identified by the licensee or detected by CNSC staff, the regulated party is expected to address or correct the situation promptly. If necessary, the CNSC may also take enforcement action to compel compliance with regulatory requirements.

7.3 Enforcement

The purpose of enforcement is to compel licensees or regulated persons back into compliance where non-compliance is detected. The CNSC does not take enforcement action to punish, but rather to encourage compliance, to maintain continued safety, and to deter further non-compliance.

The CNSC uses a graded approach to enforcement. Regulated parties typically identify and self-correct non-compliances on an ongoing basis; however, where enforcement is indicated, the appropriate enforcement action for the given situation is determined, taking into account such considerations as:

- the risk significance of the non-compliance with respect to health, safety, security, the environment and international obligations

- the circumstances that lead to the non-compliance (including acts of willfulness)

- the compliance history of the regulated party

- operational and legal constraints (for example, the Directive to the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission Regarding the Health of Canadians)

- industry-specific considerations

Enforcement actions include informal discussion, orders, administrative monetary penalties and legal prosecution. Any enforcement action can be used independently or in combination with others, resulting in a wide range of options available to the CNSC.

7.4 Compliance reporting

CNSC staff report to the Commission, the public, licensees, the Government of Canada, the International Atomic Energy Agency, and other interested parties on the results of compliance verification and enforcement activities. Compliance reports document the safety performance of regulated activities, and are based on the CNSC’s independent evaluation of compliance and licensee performance.

Appendix A: Consideration of Cost-Benefit Analysis

When the CNSC reviews proposals from applicants and licensees, or receives feedback from stakeholders on regulatory matters, there may be more than one acceptable approach to address a safety objective. It is in this context that CNSC staff may consider reviewing information on costs or benefits. The submission of cost-benefit analyses by applicants, licensees, other stakeholders or Indigenous peoples is optional and voluntary on their part. To ensure that safety is not compromised, proposed approaches considered in these analyses must retain the same level of safety. This appendix provides general information on preparing a cost-benefit analysis for submission to the CNSC for regulatory matters. Further, it provides information on the consideration of cost-benefit information submitted to the Commission or a designated officer for licensing decisions, as well as information regarding the consideration of costs and benefits by the CNSC for the development of regulatory documents. The end of this appendix some example methodologies and resources for the performance of a cost-benefit analysis.

The CNSC does not endorse any specific cost-benefit methodology, nor does it limit cost-benefit analysis to any specific SCA. Cost-benefit information submitted on regulatory matters should be verifiable, replicable and fit for purpose.

A.1 Considerations when preparing a cost-benefit analysis

In carrying out the mandate of the NSCA and associated regulations, the Commission and/or CNSC staff will consider any relevant information submitted by applicants, licensees, members of the public, Indigenous peoples and other stakeholders with respect to regulatory or licensing processes. This includes cost-benefit information related to an alternate proposal to meet regulatory requirements. Cost-benefit information may be either quantitative or qualitative in nature. Stakeholders and Indigenous peoples should consider the following when preparing cost-benefit information:

A.1.1 Level of analysis

The level of analysis should be commensurate with the nature of the decision that needs to be made. In general, minor routine decisions with minor potential consequences should not demand the same level of analysis as exceptional decisions having major potential consequences. If investing in more data, research or analysis is not expected to change the ranking of alternatives, further investment is not justified.

A.1.2 Rationale

The rationale should clearly set out the problem or opportunity that is being addressed and the desired outcome. A clear rationale statement provides a good foundation for identifying reasonable alternative courses of action and for determining whether each alternative is capable of satisfying the purpose of a proposed action or project.

A.1.3 Boundaries

Boundaries for the evaluation (such as time period and geographical area) should be described precisely and a compelling rationale provided to explain why they were selected. A key measure of the reasonableness of decisions on boundaries is evidence that expanding or contracting the boundaries of an evaluation would not likely change the ordering of the alternatives.

A.1.4 Potential factors for consideration in the cost-benefit analysis

Depending on the nature of the decision being taken, in addition to an analysis focused on the proponent, it may be appropriate to consider other factors during the analysis, such as human health and the environment. In all cases, information provided should be relevant to the CNSC’s regulatory responsibilities.

A.1.5 Consideration of alternatives

An essential requirement for good decision making is a full consideration of all reasonable options. Including a comprehensive range of reasonable alternatives is also essential to demonstrating that an analysis is unbiased. The following should be considered:

- Have possible alternatives for addressing the problem or opportunity been identified and listed?

- Have reasonable alternatives been analyzed?

- Has each alternative been developed to a reasonable level of detail for a sufficiently accurate evaluation of costs and benefits to reliably distinguish among the alternatives?

- Has each alternative been designed using an unbiased and consistent approach?

- Has the analysis of each alternative been comprehensive and based on a common set of data, relationships and assumptions?

- Should the status quo (i.e., do nothing) alternative be considered? This option may not be applicable in cases where the CNSC has established an objective that must be met.

A.1.6 Forecasting

Forecasting involves the prediction or estimation of the future costs and/or benefits for the selected course of action. Forecasting the expected impact of an alternative course of action may involve many disciplines (e.g., engineering, environmental sciences) and many different types of data (e.g., biophysical, engineering, social). Any assumptions regarding the selection of conditions for the future forecasts should be clear, well-explained and based on realistic evidence.

A.1.7 Valuation

Valuation involves estimating the relative importance of a risk, cost or benefit; in economics, market prices and imputed market prices are often used for valuation. In multi-criteria decision analysis, valuation is undertaken through participatory processes. Extensive literature dealing with appropriate valuation and accounting methods exists. Cost-benefit information should explain and rationalize the valuation method(s) that have been used for risks, costs or benefits.

A.1.8 Value-based weighting

Valuation or assigning a score to an alternative for a given criterion can be modified by a weighting factor, typically based on value judgments. Providing these value-judgment weightings increases the transparency of the stakeholder’s or Indigenous peoples’ decision making toward its preferred alternative.

A.1.9 Uncertainty

Uncertainty can result in the actual outcome being above or below the expected outcome. The cost-benefit analysis should include a systematic and comprehensive uncertainty analysis.

A.1.10 Sensitivity analysis

An analysis may be based on many individual data points, relationships and assumptions; however, a small subset of these may have a disproportionate influence on the overall evaluation of alternatives. Knowing which data, relationships and assumptions have the greatest influence on the overall result is important from a decision-making perspective.

Sensitivity analysis is valuable in deciding whether more investment in data collection and research is warranted before a decision on a project is made. Cost-benefit information should include a sensitivity analysis that ranks key data points, relationships and assumptions relative to their impact on the results of the evaluation of alternatives. Of particular importance is to identify those data points, relationships and assumptions that are likely to alter the final ranking of the alternatives.

Sensitivity analysis, however, can be essentially open-ended with larger projects involving many data points, relationships and assumptions. Prudence and judgment are required to balance demands for more sensitivity analysis with the likelihood of new insights being provided. The cost-benefit analysis should provide a compelling rationale for the limits to the sensitivity analysis conducted.

A.1.11 Replicability

An analysis is considered replicable if a qualified third party would be able to duplicate the evaluation of alternatives and reach the same conclusion using the same data and methods. Thorough, clear and accessible documentation that includes all data, sources, forecasting methods, assumptions and calculations are critical for replicability.

A.1.12 Discount rate

Discounting allows for the calculation of costs and benefits that occur over several years, taking inflation and other factors into account. Choosing an appropriate discount rate is an important consideration because it will affect the calculation of net costs and benefits and potentially have an impact on the conclusion. In all cases, the discount rate used in the analysis should be clear.

A.2 Considerations of costs and benefits for licence applications and decisions

The Commission makes independent and transparent decisions on the licensing of nuclear-related activities in Canada. When making a decision under the NSCA, the Commission or its designated officer will consider any relevant information submitted by licensees, applicants, Indigenous peoples or other stakeholders. This includes cost-benefit information related to an alternate, acceptable proposal to address a safety objective and/or meet regulatory requirements. It is in this context that CNSC staff may consider reviewing information on costs or benefits. However, CNSC staff will not perform any cost-benefit analyses with respect to licensing matters, as the CNSC does not have any economic mandate under the NSCA. The submission of cost-benefit analyses by licensees, applicants, Indigenous peoples or other stakeholders in support of a licensing process is optional and voluntary on their part, and the proposed approaches considered in those analyses must retain the same level of safety in all cases. The consideration of the cost-benefit information is not limited to any specific SCA or other matter of regulatory interest during the licensing process.

A.3 Considerations of costs and benefits in regulatory documents

CNSC staff develop regulatory documents (REGDOCs) to help clarify the CNSC’s expectations for compliance with acts, regulations and licence conditions.

Request for Information statements are posted with draft regulatory documents issued for public consultation. Request for Information statements outline additional background information, the document’s objectives, and the proposed regulatory approach. Stakeholders and Indigenous peoples are also invited to identify any potential impacts (including financial impacts) and/or any proposed alternative approaches that meet the safety objectives set out in the proposed document.

The CNSC considers all comments received from stakeholders and Indigenous peoples, including any cost-benefit information submitted, as it finalizes its regulatory approach.

When establishing the deadline for the submission of comments on regulatory documents, CNSC staff will consider the time that may be required for the preparation of submissions on the costs and benefits related to the draft regulatory document.

A.4 Examples and resources for developing a cost-benefit analysis

The following resources are available to help in the development of a cost-benefit analysis:

- The CNSC must meet the requirements set out in the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s Policy on Cost-Benefit Analysis when conducting an analysis as part of the development of regulations. The policy is supported by the Cost-Benefit Analysis Guide, which provides detailed guidance.

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Standard Cost Model is a quantitative methodology that can be applied in all countries at different levels to determine the administrative burden on business imposed by regulations. This model was used by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat for its Regulatory Cost Calculator.

- Environment Canada’s Guidelines for the Assessment of Alternatives for Mine Waste Disposal can assist applicants in selecting the most suitable mine waste disposal alternative from an environmental, technical, economic and socio-economic perspective.

- CSA Group standard N290.19, Risk-Informed Decision Making for Nuclear Power Plants, describes the risk-informed decision-making process with respect to nuclear power plants. In particular, Annex B of that document contains guidance on the conduct of cost-benefit analysis for the nuclear industry in Canada.

- The document Multi-Criteria Analysis: A Manual, published by the United Kingdom Department for the Environment, Transport and the Regions, provides guidance on how to undertake multi-criteria analysis for the appraisal of options for policy and other decisions, including but not limited to those having implications for the environment.

- The International Civil Aviation Organization has developed guidance material to assist its member states conduct cost-benefit studies for identifying cost-effective technical solutions.

- The Guide to Benefit-Cost Analysis in Transport Canada provides guidance on how to evaluate the economic merits of alternative expenditure proposals using cost-benefit analysis.

- The Society for Benefit-Cost Analysis’ Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis publishes studies on the costs and benefits of regulatory actions.

- The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) technical document TECDOC-1279, Non-Technical Factors Impacting on the Decision Making Processes in Environmental Remediation, considers such factors as cost, planned land use and public perception.

- The article "Application of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis in Environmental Decision Making", published in the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry’s Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management journal, presents a review of the available literature and provides recommendations for applying multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) techniques in environmental projects.

- The book Comparative Risk Assessment and Environmental Decision Making (Linkov, I. and Ramadan, A., eds., at pp.15–54) describes how the use of comparative risk assessment can provide the scientific basis for environmentally sound and cost-efficient policies, strategies and solutions to environmental challenges.

- CSA Group standard CAN/CSA-Q850-97, Risk Management: Guidelines for Decision Makers, provides risk management guidance to help organizations plan for the potential outcomes of future events when the exact outcomes are not known.

- IAEA technical document TECDOC-1309, Cost Drivers for the Assessment of Nuclear Power Plant Life Extension, provides a methodology to determine the necessary cost inputs for the performance of a cost-benefit analysis for the life extension of nuclear power plants.

- The Nuclear Energy Agency document PSA Based Plant Modifications and Backfits (NEA/CSNI/R(97)6) provides knowledge to experts on the role of Probabilistic Safety Assessment in plant modifications with respect to safety decision making.

- The United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission (USNRC) report Estimates of the Financial Consequences of Nuclear-Power-Reactor Accidents (NUREG/CR-2723) provides preliminary techniques for the estimation of the financial consequences, including both onsite and offsite costs, of potential nuclear reactor accidents.

- The USNRC document A Handbook for Value-Impact Assessment (NUREG/CR-3568) documents a set of systematic procedures for providing information for performing value-impact assessments, and the process for performing such an assessment.

- The USNRC report Cost-Benefit Considerations in Regulatory Analysis (NUREG/CR-6349) provides information on the value-impact analysis for safety enhancements of nuclear facilities as well as the monetary value of the averted radiation dose (dollars/person-rem).

Appendix B: Safety and Control Area Framework

The CNSC’s regulatory requirements and expectations for the safety performance of programs are organized into a framework made up of 3 functional areas and 14 safety and control areas (SCAs), which are subdivided into specific areas. Table B outlines each functional area and their respective SCAs and specific areas.

| Functional area | Safety and control area | Specific area |

|---|---|---|

| Management | Management system | Management system |

| Organization | ||

| Performance assessment, improvement and management review | ||

| Operating experience (OPEX) | ||

| Change management | ||

| Safety culture | ||

| Configuration management | ||

| Records management | ||

| Management of contractors | ||

| Business continuity | ||

| Human performance management | Human performance program | |

| Personnel training | ||

| Personnel certification | ||

| Initial certification examinations and requalification tests | ||

| Work organization and job design | ||

| Fitness for duty | ||

| Operating performance | Conduct of licensed activities | |

| Procedures | ||

| Reporting and trending | ||

| Outage management performance | ||

| Safe operating envelope | ||

| Severe accident management and recovery | ||

| Accident management and recovery | ||

| Facility and equipment | Safety analysis | Deterministic safety analysis |

| Hazard analysis | ||

| Probabilistic safety assessment | ||

| Criticality safety | ||

| Severe accident analysis | ||

| Management of safety issues (including R&D programs) | ||

| Physical design | Design governance | |

| Site characterization | ||

| Facility design | ||

| Structure design | ||

| System design | ||

| Component design | ||

| Fitness for service | Equipment fitness for service / equipment performance | |

| Maintenance | ||

| Structural integrity | ||

| Aging management | ||

| Chemistry control | ||

| Periodic inspection and testing | ||

| Core control processes | Radiation protection | Application of ALARA |

| Worker dose control | ||

| Radiation protection program performance | ||

| Radiological hazard control | ||

| Estimated dose to public | ||

| Conventional health and safety | Performance | |

| Practices | ||

| Awareness | ||

| Environmental protection | Effluent and emissions control (releases) | |

| Environmental management system (EMS) | ||

| Assessment and monitoring | ||

| Protection of the public | ||

| Environmental risk assessment | ||

| Emergency management and fire protection | Conventional emergency preparedness and response | |

| Nuclear emergency preparedness and response | ||

| Fire emergency preparedness and response | ||

| Waste management | Waste characterization | |

| Waste minimization | ||

| Waste management practices | ||

| Decommissioning plans | ||

| Security | Facilities and equipment | |

| Response arrangements | ||

| Security practices | ||

| Drills and exercises | ||

| Cyber security | ||

|

Safeguards and non-proliferation |

Nuclear material accountancy and control | |

| Access and assistance to the IAEA | ||

| Operational and design information | ||

| Safeguards equipment, containment and surveillance | ||

| Import and export | ||

| Packaging and transport | Package design and maintenance | |

| Packaging and transport | ||

| Registration for use |

Appendix C: Levels of Defence in Depth for Nuclear Power Plants

Defence in depth is a principle implemented primarily through a combination of multiple consecutive and independent levels of protection. For nuclear power plants, defence in depth consists of different levels of equipment and procedures to maintain the effectiveness of physical barriers placed between radioactive materials and workers, the public or the environment. Table A shows an example of the objectives and implementation of each level in a defence-in-depth regime for a nuclear power plant.

| Level | Objective | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Normal operation: To prevent deviations from normal operation, and to prevent failures of structures, systems and components (SSCs) important to safety. |

|

| 2 | Operational occurrences: To detect and intercept deviations from normal operation, to prevent anticipated operational occurrences from escalating to accident conditions, and to return the plant to a state of normal operation. |

|

| 3 | Design basis accidents: To minimize the consequences of accidents and prevent escalation to beyond design basis accidents. |

|

| 4 | Beyond design basis accidents: To ensure that radioactive releases caused by beyond design basis accidents, including severe accidents, are kept as low as practicable. |

|

| 5 | Mitigation of radiological consequences: To mitigate the radiological consequences of potential releases of radioactive materials that may result from accident conditions. |

|

Source: Implementation of Defence in Depth at Nuclear Power Plants: Lessons Learnt from the Fukushima Daiichi Accident, NEA No. 7248, 2016 [10].

Appendix D: Risk-Informed Regulating

Introduction

To regulate an evolving nuclear sector, the CNSC maintains an effective and agile Regulatory Framework. The CNSC considers risk using the best available data and science in all regulatory activity undertaken by the organization. This approach considers the level of risk to health, safety, security and the environment as the basis by which to establish regulatory requirements, assess licence applications and ensure compliance with requirements for the conduct of a licensed activity.

D.1 Risk-Informed Approach

Consideration of risk informs all regulatory activity undertaken by the CNSC. Risk is factored into the CNSC’s regulatory framework as well as its licensing, compliance and enforcement activities.

Examples of how the CNSC regulates in a risk-informed manner are:

- applying risk information to the development of requirements across all regulated activities

- ensuring risk-informed requirements are reflected in the planning, scoping and prioritization of oversight activities

- using national and international standards to analyse and inform the assessment of risk for a specific activity or facility

- applying requirements and guidance in a graded manner commensurate with the level of risk of the regulated activity

- having a regulatory framework that allows applicants and licensees to propose alternative methods to meet regulatory requirements where appropriate

In reviewing licence applications, the CNSC considers the licensees’ processes and operational plans to undertake activities in accordance with a specified risk. In defining the licensing basis, the Commission also considers risk when setting licence terms, conditions and requirements. Further to this, risk considerations are taken into account where stricter enforcement action is applied for non-compliance against higher-risk activities. Activities with the highest risk profile receive the highest level of regulatory oversight. While taking a risk-informed approach, applicants and licensees must maintain sufficient levels of safety and security under all conditions by complying with regulatory requirements. Two important aspects of risk-informed regulation are the application of a graded approach and flexibility to consider alternative approaches to meeting requirements.

D.1.1 Graded approach

The IAEA Safety Glossary defines Graded Approach as follows: “For a system of control, such as a regulatory system or a safety system, a process or method in which the stringency of the control measures and conditions to be applied is commensurate, to the extent practicable, with the likelihood and possible consequences of, and the level of risk associated with, a loss of control.”

The IAEA definition further states: “The use of a graded approach is intended to ensure that the necessary levels of analysis, documentation and actions are commensurate with, for example, the magnitudes of any radiological hazards and non-radiological hazards, the nature and the particular characteristics of a facility, and the stage in the lifetime of a facility.”

The CNSC in turn defines Graded Approach as “a method or process by which elements such as the level of analysis, the depth of documentation and the scope of actions necessary to comply with requirements are commensurate with:

- the relative risks to health, safety, security, the environment and the implementation of international obligations to which Canada has agreed

- the particular characteristics of a nuclear facility or licensed activity”

Using a graded approach, the CNSC conducts an assessment of a safety case for a proposed activity to ensure regulatory requirements and safety objectives are met.

The graded approach is the application of regulatory requirements in a risk-informed manner and may consider some of the following, depending on the activity:

- safety characteristics

- fuel design and source term

- amount and enrichment of fissile and fissionable material

- presence of high-energy sources, and other radioactive and hazardous sources

- uncertainties associated with the regulated activity

- site characteristics (e.g., external hazards)

Activities with greater risk require stronger risk mitigation measures. For example, where there is greater uncertainty on facility operation, more stringent measures for containment, control and cooling, additional instrumentation, increased inspection frequency or a more restrictive operating envelope may be needed.

Conversely, where there is less risk, less stringent mitigation measures may be adequate to achieve desired outcomes of fulfilling fundamental safety functions. For example, the inherent risk levels between a small research reactor such as SLOWPOKE-2 (20 MW thermal) and a large reactor designed for electricity generation (800 MW thermal), are significantly different. The use of the graded approach to regulating results in the application of measures that are proportionate to the risk of the facility.

D.1.2 Alternative approach

An applicant/licensee can propose alternative approaches to meet regulatory requirements. The applicant/licensee must demonstrate that the proposed alternative meets the overarching safety requirement.

Examples of alternative approaches include:

- application of national or industry codes and standards from other jurisdictions

- use of an approach or application proven in another industry but not yet commonly applied to the nuclear sector

- introduction of innovative or new technologies